“Re-Corte” Catálogo, Galería Animal, diciembre 2008.

Why did you choose water as the central theme of your work?

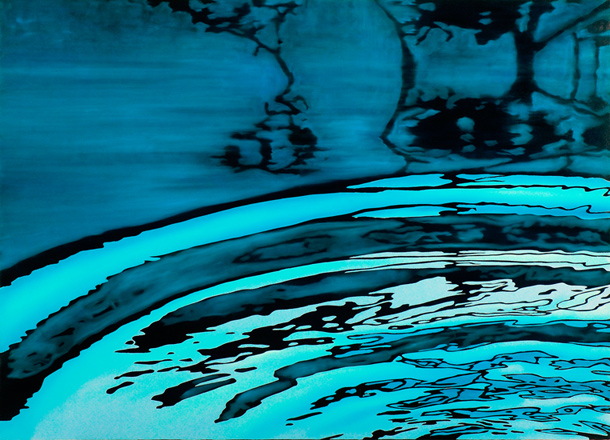

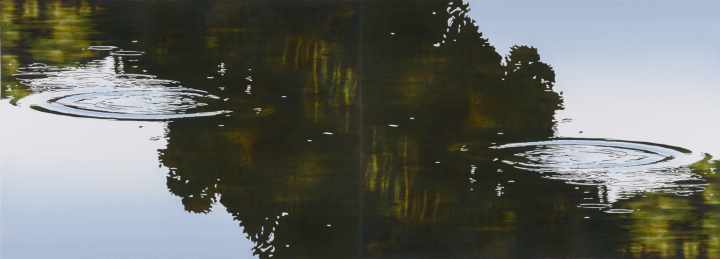

Water is an infinite source of images, a stage of movement that second to second reflects its surface like a mirror. Besides, that characteristics of its materiality allows me to abstract, play and change its rules, giving me the artistic freedom necessary to follow my aesthetic objective. I fix my gaze on water with a close environment that fills with color, transparent water, with capacity to mirror and reflect. This allows me to work the duality between light and shade, achieving the unity of the image representing the landscape.

In some way, water is the element of nature that permits one to transcend it in a way, to go deeper. What quality of water makes this dynamic possible?

In its external form, water is not definite. It is an absence that takes its presence from its environment. It needs something separate to manifest itself as it has no color, nor specific form. Upon recovering the image submitted and taking it to my studio, I also bring with me an absence. The water is no longer there. There are colors and the idea of an image that will end up being water again but in the form of an illusion.

The water projects everything around it, uniting various planes of the surroundings within.

Its a transfer medium: an image for processing is submitted, translating the landscape so it can be contemplated in its totality. This method of seeing the landscape “through” is similar to the actual look, from the twenty first century, to the world: a virtual approach through media.

The water, transformed in a natural mirror, gives us the first image “mediatized” from the surroundings, as if its gaze is naturally inserted in the modernity. The image is already reflected on the water screen and the photographic capture is a “re-mediatization” of the image.

Would it be possible to obtain this collection of instants from another source?

I don’t think so, because the visual that I record through painting I find only in a surface in movement or liquid territory. The movement is what permits the duality that gives expression to in my work: to see through the shadows of the environment the colors that reveal what is in the depths, and the reflection of the exterior on the surface by the light. The mobility creates the ripples allowing the contrast of mask-background and light-shadow, fundamentals in the construction of the illusion in the piece.

If the water is too quiet, I can disturb it with a stone, a drop or the oar of a boat. I need the movement so the surface of the water produces a mosaic effect and in it is found another luminosity.

You say that the duality, the co-existence of opposites, is one of the defining characteristics of the water you paint. How do you manage to translate this double reality to a single plane?

The reconstruction of the whole starting from the duality is achieved by breaking down the image, literally making two paintings. First, I dedicate myself to the background that I build by layers annulling the texture of the canvas: with a smooth thickness of pictorial matter I work including the refracted image form the water in the matter, in the paste. The second painting is the reflected image. The movement and light are what are drawn, posed over the shadow of the background. This strong light, produced by tan angle change or movement is painted masking the background that exists physically underneath the painted reflection. So, under the reflected light exists a background of water that is the background of the painting.

The technique that you use allows you to represent three planes present in the water: the water itself or its body, the exterior landscape, and its bottom. You reconstruct the three-dimensionality of the water that the human eye does not perceive simultaneously.

That is the central thesis of my work: the continuity after the record. To achieve this the use of virtual and digital media is fundamental. The camera allows me to register more information than that which the eye can retain. The photography that captures the sequences of the waves contains “multiple information” for processing. The instantaneous record allows me to identify and separate the different elements that are present in the frozen instant. Using the craft of the technology, I can deconstruct the image and later rebuild it.

Another characteristic of your paintings is the difference between the close and distant view.

That is given through the work of the technique that acts as a trap: from far away is appears like photo-realism, where the painting is recognized as a photo, but upon approach one realizes that there is a geometric treatment, a surface of brights and opacity; an almost abstract appearance. It begins to place with the co-existence of reality and abstraction. The use of this limit will determine the presence of disappearance of the water concept.

To maintain oneself on the edge must mean a risk, a vertigo.

Attempting to work on a detail is already risky, and the waves can be very abstract and are in danger of being lost. I stay connected to the color to give the suggestion of reality and I try to produce a 1:1 scale with the place: this contributes to the final dialogue of the work with the viewer. Both views, distant and closeup are proportionally scaled to the human eye.

Is the view and its possibilities what define your proposal?

The view of the detail is central to my work, detail that is shown as a total and forms the base of the concept pictorial synecdoche. I take the water as landscape and through this element I name the surroundings.

What is more, there exists a vertical view to the horizontal scene that represents the water obligating me to change my point of view to be able to arrive at its depths. This new view complements the idea of synecdoche, to permit the integration of the landscape and the different elements of which it’s made.

You mentioned that the water and its characteristics gives you the formal liberty you need to paint. This idea of freedom of form resonates with the definition of beauty by Schiller: “It is beauty that has the appearance of freedom”.

The freedom of movement and the forms produced in the water are the creative inspiration that allow the technical freedom; but behind this liberty is the essential, where the opposites are sustained in a permanent equilibrium.

This visual freedom suggests and idea of beauty related with the transcendence of the duality present in water.

The water is a totality uniting opposites manifested in different planes. The harmony and beauty is created by the fusion of the darkness of the depths with the brilliance of light on its surface. Also, through the coincidence of the form with the bottom that gives integrity to the landscape.

For eastern landscapers, the painting allows one to look at their own interior, suggesting that the representation of landscape has a direct relationship with who we are. In this way, the whole represented beginning with the present duality in water is a reflection of human nature, also dual and integrated at the same time. The difference with the oriental would be in the choice of detail that obliges one to abstract and arrive at the essential that later is extended as a whole, ceasing to be the description of a specific location.

Would you place yourself in the traditional group of landscape artists?

Water is an element of the landscape, so in this way I am a landscape artist. However, I create a reinterpretation of the landscape from a new focus, looking from the detail to the whole. Besides that, I work with technique in an experimental way.

Who would be references for you?

I have historical influences, such as Leonardo, of whom I have read a lot and always admired for his technique and capacity for analysis. His study of water includes more than just color: interested in waves, he analyzed its luminous capacity, the reflection and refraction though it. I cite it in my work in the smears and the velatures with which I build the images of the backgrounds. Also Monet, for his treatment of shadow in the reflection of landscape in the water.

Other references are connected with the current interrogations of the painter: How does one reinterpret an image processed through media that creates a personal reality from the painting? Why paint if photography registers the reality with insuperable precision? Vija Celmins with his details, Chuck Close with his faces and Gerhard Richter with his pictorial liberties have responded through their works. In them their central inspirations revealed is the painting and the human touch that from them is processed their own reality. We coincide in a sensibility of time, where the eye of the painter is behind the medias.

From another visual language, a contemporary artist bound to the landscape is Olafur Eliasson, who with very experimental methods approaches the viewer to the luminous sensations and atmospheres of the exterior, translated to the interior of an exhibition room; like bringing water physically to the museum. I do this with an illusion, however we fix the gaze on the same element.

Do you consider yourself part of the Land Art trend?

Historically, Land Art was an important moment for landscape in art. They leave the gallery room and the studios and go directly to the place to work, with the elements that are there, presenting their work as a record of this intervention. They marked a trend and were a defense for sculpture, photography and installations related with the landscape. I do not intervene the water as they intervene the earth, but the act of going to the place, studying it for days establishes a similarity between me and this trend.

The video that accompanies the exposition is part of your experimentation over water and its liberties?

The video investigated the reflective capacity of the water from another visual medium. I exercised seeing what really happened upon re-mirroring the water upon turning around the image. Highlighting the dualism between the movement of the upper part of the current, the light, and the refracted part of the shade that remains static, fusing them together in a single image.

Your work is a piece of time in nature…

That recorded instant on this natural screen claims a new time in the pictorial process, being the strategy of return that allows us to contemplate the human convention that we encode as landscape. It is my own form of recreating nature through the infinite source of image and life that is water.

References:

– Schiller, Friedrich. Kallias o sobre la belleza. Editorial Tecnos. Primera edición. Madrid, 2000. P. 16. 249 pp.