Instalation at Saval Laboratories

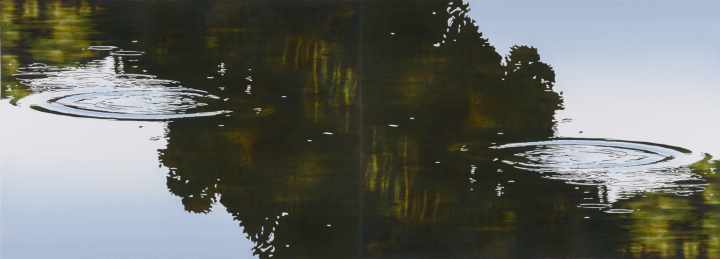

At Saval Laboratories in Santiago, Chile, there is this instalation of this digital piece based on a painting about the reflections of the Bueno river.

At Saval Laboratories in Santiago, Chile, there is this instalation of this digital piece based on a painting about the reflections of the Bueno river.

María Olga Giménez

““…How nice it would be if we could only get through into Looking-glass House!

I’m sure it’s got, oh! such beautiful things in it! …

Let’s pretend the glass has got all soft like gauze,

so that we can get through! …

It’ll be easy enough to get through!

…In another moment Alice was through the glass,

and had jumped lightly down into the Looking-glass room.”

Water is nature’s looking glass, and is unique in its double capacity to mirror: from the light and through the shade. Considering that water makes up three quarters of the world and our bodies contain approximately the same proportion, we understand that each person has a mirror inside themselve that reflects with the same quality. The work of Patricia Claro naturally invokes out capacity to speculate, moving us to go beyond the surface of the mask in a similar way as Alice, using imagination and dreams. This entrance to the dream realm in art, particularly in landscape art, was recognized by Gastón Bachelard in 1942, who sustains that: “Only the landscapes we have seen first in our dreams are the ones we see with an aesthetic passion” .

Her creative process begins with a journey to the water where one always finds the same characteristic: they will be clear waters that mirror and reveal a calm and permanent movement. These waters act as an infinite source of different images submitted in each moment.

The water is the origin of the process, the first lens. The artist’s participation starts by mirroring herself, saving oneself from the gaze of Narcissus to allow that both mirrors are recognized and extend into their immensity. Here it is necessary to capture this moment by means of digital photography; to detain the scene in movement and conserve the sequence of fleeting reflections. The image chosen for the second lens of the process may contain one or more of the elements that will be represented in the pictoric work: the exterior landscape, of which the trees, a branch or the sky may form; and the interior landscape made by the depths of the water. It can also be present in the water itself, with its currents in the form of waves or its apparent stillness.

At the moment of reconstituding the materiality of the water or its body, brings out the importance of the existence of the movement within. This body depends on the possible refraction of light -that reveals the exterior-, or the presence of the shade, resulting from an external object -that reveals the interior. It is the product reflection of the movement of the water that permits the light to cover that which the shade reveals of the depths, acting as a veil. This play of light and shade creates a reversibility of the image that is appreciated at the inversion of the position of the painting: we see the sky that is water and a landscape of water and green that is sky.

Water clipping: and entrance into the time of nature

The photography taken on site represents an incision of death in the time of the water that freezes its flow. Lather, the process of cropping in the studio prolongs this action. Then it would be fitting to ask about the relationship that exists between the crop and the mirror.

“Mirrors: to this day, no expertise can explain

the key to what you truly are;

filling the interstices of time’s plane

with mere holes as from a colander.

Spendthrifts of the vacant foyer —

wide as woods beneath twilight stars. ..

And the chandelier bounds like a sixteen-pointer

through your impenetrability.

Sometimes you are filled with canvases.

Some even seem absorbed into your depths —

other styles you timidly dismiss.

But the loveliest remains, until appears

Narcissus to press her chaste lips,

fully liberated and crystal clear.”

The poet Rainer Maria Rilke brings us closer to the answer: the mirror represents an interval of time, a cut in the linearity of the life it reflects. The water is part of the nature, whose time is circular and we share, in part, this indeterminable cycle of life and death. For this reason, when the artist is reflected in front of it, it creates a point of refraction between them that permits one to transfer the images beyond time. This makes possible that the sequence of clippings contributes to capture the final image of the water represented in the picture.

Claro’s technological eye is key in her “reflective” process. In a true virtual laboratory work, making use of digital programs, the image that will be the underlying layer of the work is translated through media. This third clipping of water understands the deconstruction and decomposition of the image in its basic geometric forms isolating the color, light and shade. It is significant that this work is realized as opposite the original: it is the machine -created by man- that has the capacity to isolate the elements of the natural landscape. bringing it to its state of primitive chaos.

The work in the studio constitutes a true reflective contemplation that captures time brushstroke by brushstroke. The canvas receives the image progressively, beginning with the light and continuing to the depths of to conforming the pictorial materiality. This is the reflective time of the artist, different than that of the water that mirrors in an instant. We see that three times exist in the work of Claro: the time of the water, the frozen instant; the time of the creative process; and the time of the viewer when they face the work that already makes a mirror.

Among those postulating from Land Art, Robert Smithson signals the existence of a relationship “between the earths surface, its features, etc., and the fallacies of though and fictions of the spirit. The sinking earth, the flaws, etc., are not produced solely in nature as in the human mind.” This idea affirms that the systematic process of destruction of the initial image corresponds with the crystallization of its impression on the subconscious of the artist as well as its reconstruction states the return to the consciousness of that image. the metaphor of the mirror represents this principal: the shadow of the water is the shadow of the mind, the subconscious, the unknown with respect to itself, and the light reflected is the identity of self.

We then have an image that begins with the water of nature and continues in the waters of the mind to emerge again as water in the piece, forming a trinity: water – mirror/mind – water.

The abstraction process to the image represents a conceptual reduction, based on bringing the imaged to their universal forms to later begin its appropriation on the canvas. The different cuts create the abstraction: the photographic, the framing in photoshop, and the clippings of the mask. Afterward, the layer of the reflection finishes the process, restoring the unity of the image.

The particular reconstruction of the landscape beginning from a selection of water represents a pictorial synecdoche, central concept in Patricia Claro’s proposal. The poetic subjectivity of the artist is incorporated through the feminine gaze toward a detail that is re-constitude. “Perhaps there does not exist an individuality in depth that makes the matter, in its smallest parts, be always a totality?” .

The result of this process is the work we have in front or us, that provokes the following question: How does our own mirror act in front of these waters?

The originality of the artist is manifested in the change of focus or gaze to the exterior, that goes from horizontal to vertical, similar to the view see by a satellite. This vertical gaze makes a global perception of nature and man possible, situating us in front of a grand horizontal mirror that transfers the surroundings in an infinite process: the water. This unitarian perception of the world is united to its technological look in respect to the handcraftedness and creative process implying the experimentation of traditional techniques and the use of digital medias, giving the work the multicultural connotation that places it in the contemporary world.

For Claro, the water will always be and aesthetic and poetic inspiration and source of inexhaustible composition. The video complementing the exposition is an example of this expressing the reflective capacity of the water when is mirrors itself, to be reflected and dejected at the same time. Also the group of works exhibited horizontally on the floor of the gallery permit the spatial return of the water to its natural place.

The spectator confronts the simultaneity of realism and abstraction: the distant gaze allows a realistic perception of the piece, while closer inspection reveals a collection of textures, marks and relief that makes up the materiality of the work. This experience concludes the reflective process initiated by the author, returning to the original time of the first instant of activating the reflection of another mirror.

• Bachelard, Gaston. El agua y los sueños. Ensayo sobre la imaginación de la materia. Fondo de Cultura Económica. Primera edición en español. México, 1978. 295 pp.

• Carrol, Lewis. Alicia en el país de las Maravillas. A través del Espejo. Editorial Cátedra. Quinta edición. Madrid, 2001. 388 pp.

• Claro Swinburn, Patricia. Corte y Reconstitución del paisaje: una Sinécdoque pictórica. Memoria de Grado presentada a la Escuela de Arte de la Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile. Santiago de Chile, 2005.

• Diccionario de la Real Academia Española. Tomo I. Vigésimo segunda edición. Madrid, 2001. 1180 pp.

• Gombrich, E. H. La Historia del Arte. Editorial Debate. Edición número 16. Londres, 2006. 688 pp.

• Guasch, Anna María. Las vanguardias del siglo XX. Del posminimalismo a lo multicultural: 1968-1995. Ed. Alianza. Madrid, 2000.

• Rilke, Rainer Maria. Los sonetos a Orfeo. Traducción de Otto Dörr Zegers. Editorial Universitaria. Primera edición. Santiago de Chile, 2002. 219 pp.

Arts and Letters

Sunday December 28, 2008

Patricia Claro y Ricardo Maffei:

WALDEMAR SOMMER

Amongst ourselves we frequently don’t trust the realisms of the present age. There are several reasons for this that are worthy of consideration. These vary from the lack of synthesis, responsible for the boring accumulation of details, to the grave subordination of the formal narrative values. All this is translated to the inability of suggestions and the excess of evidence. Luckily, we can count with a few painters loyal to a recognizable reality. They are able to transcend it with valid insinuations. Two of them, completely different from one another, are being exhibited during these days. One is in at the beginning of her trajectory while the other is in the middle of his production.

Let’s start with the first one. She depicts the calm and flow of waters with its lights and shadows, brightness and transparencies, with reflections of its surroundings. This is the genuine theme of Patricia Claro which is now being shown in Galería Animal. It is reduced to nine big paintings and one great horizontal triptych. There is also a video with a very adequate sonorous support whose notes are prolonged in different planes and where the sound of water welds with electronic music.

In the ways of impressionists, an affectionate study of aquatic nature appears in these oil paintings on fabric. Sometimes, the placid and watery blue surfaces, with touches of green and black, pick up the surrounding leafy vegetation and makes it its own. It also adds its own tones of green, ocher and orange. They probably capture de most beautiful examples of the exhibition.

On the other hand, Ricardo Maffei shows recent pastels on paper (2004-08) in the Galería A.M. Malborough. If before he drew attention by his small cup of color over wrinkled paper theme, now he undertakes seven developments over that argument, making it richer. Now, the round hard object lies over cloth and over marble. He sometimes confronts a crushing machine or a glass of water.

Other characters of his are the morbid superposed fabrics where the exquisite sensuality of the diagonal folds seems to talk to the extended quilts in a game of horizontals and verticals, of straight and curved lines and of false contrasts in the material. With this, the present still life transcends the anecdote through an effective reinforcement of the plastic ingredient. Maffei also stands out in two other aspects. Unlike the most famous realist Chilean painter, we have his impeccable administration of cuts and limits of each one of his frontal visions.

As far as color goes, his chromatic accords always emerge extremely beautiful with confrontations of complementary colors, especially of yellow and violet or violet blues. At the same time, his evocative backgrounds stand out rich with enigmatic signs, stripes and spots which introduce certain instability to the certainty of the protagonist cloth. Despite all this, the painter has never before shown a greater genuineness or visual lightness in his themes.

KEYS: Pause in the subordination that the narrative ingredients suffer, so detrimental to realism, in the hands of Claro and Maffei, managing this way to prevail the aquatic lyricism en the first one and the elegance of forms in the second.

“Re-Corte” Catálogo, Galería Animal, diciembre 2008.

Why did you choose water as the central theme of your work?

Water is an infinite source of images, a stage of movement that second to second reflects its surface like a mirror. Besides, that characteristics of its materiality allows me to abstract, play and change its rules, giving me the artistic freedom necessary to follow my aesthetic objective. I fix my gaze on water with a close environment that fills with color, transparent water, with capacity to mirror and reflect. This allows me to work the duality between light and shade, achieving the unity of the image representing the landscape.

In some way, water is the element of nature that permits one to transcend it in a way, to go deeper. What quality of water makes this dynamic possible?

In its external form, water is not definite. It is an absence that takes its presence from its environment. It needs something separate to manifest itself as it has no color, nor specific form. Upon recovering the image submitted and taking it to my studio, I also bring with me an absence. The water is no longer there. There are colors and the idea of an image that will end up being water again but in the form of an illusion.

The water projects everything around it, uniting various planes of the surroundings within.

Its a transfer medium: an image for processing is submitted, translating the landscape so it can be contemplated in its totality. This method of seeing the landscape “through” is similar to the actual look, from the twenty first century, to the world: a virtual approach through media.

The water, transformed in a natural mirror, gives us the first image “mediatized” from the surroundings, as if its gaze is naturally inserted in the modernity. The image is already reflected on the water screen and the photographic capture is a “re-mediatization” of the image.

Would it be possible to obtain this collection of instants from another source?

I don’t think so, because the visual that I record through painting I find only in a surface in movement or liquid territory. The movement is what permits the duality that gives expression to in my work: to see through the shadows of the environment the colors that reveal what is in the depths, and the reflection of the exterior on the surface by the light. The mobility creates the ripples allowing the contrast of mask-background and light-shadow, fundamentals in the construction of the illusion in the piece.

If the water is too quiet, I can disturb it with a stone, a drop or the oar of a boat. I need the movement so the surface of the water produces a mosaic effect and in it is found another luminosity.

You say that the duality, the co-existence of opposites, is one of the defining characteristics of the water you paint. How do you manage to translate this double reality to a single plane?

The reconstruction of the whole starting from the duality is achieved by breaking down the image, literally making two paintings. First, I dedicate myself to the background that I build by layers annulling the texture of the canvas: with a smooth thickness of pictorial matter I work including the refracted image form the water in the matter, in the paste. The second painting is the reflected image. The movement and light are what are drawn, posed over the shadow of the background. This strong light, produced by tan angle change or movement is painted masking the background that exists physically underneath the painted reflection. So, under the reflected light exists a background of water that is the background of the painting.

The technique that you use allows you to represent three planes present in the water: the water itself or its body, the exterior landscape, and its bottom. You reconstruct the three-dimensionality of the water that the human eye does not perceive simultaneously.

That is the central thesis of my work: the continuity after the record. To achieve this the use of virtual and digital media is fundamental. The camera allows me to register more information than that which the eye can retain. The photography that captures the sequences of the waves contains “multiple information” for processing. The instantaneous record allows me to identify and separate the different elements that are present in the frozen instant. Using the craft of the technology, I can deconstruct the image and later rebuild it.

Another characteristic of your paintings is the difference between the close and distant view.

That is given through the work of the technique that acts as a trap: from far away is appears like photo-realism, where the painting is recognized as a photo, but upon approach one realizes that there is a geometric treatment, a surface of brights and opacity; an almost abstract appearance. It begins to place with the co-existence of reality and abstraction. The use of this limit will determine the presence of disappearance of the water concept.

To maintain oneself on the edge must mean a risk, a vertigo.

Attempting to work on a detail is already risky, and the waves can be very abstract and are in danger of being lost. I stay connected to the color to give the suggestion of reality and I try to produce a 1:1 scale with the place: this contributes to the final dialogue of the work with the viewer. Both views, distant and closeup are proportionally scaled to the human eye.

Is the view and its possibilities what define your proposal?

The view of the detail is central to my work, detail that is shown as a total and forms the base of the concept pictorial synecdoche. I take the water as landscape and through this element I name the surroundings.

What is more, there exists a vertical view to the horizontal scene that represents the water obligating me to change my point of view to be able to arrive at its depths. This new view complements the idea of synecdoche, to permit the integration of the landscape and the different elements of which it’s made.

You mentioned that the water and its characteristics gives you the formal liberty you need to paint. This idea of freedom of form resonates with the definition of beauty by Schiller: “It is beauty that has the appearance of freedom”.

The freedom of movement and the forms produced in the water are the creative inspiration that allow the technical freedom; but behind this liberty is the essential, where the opposites are sustained in a permanent equilibrium.

This visual freedom suggests and idea of beauty related with the transcendence of the duality present in water.

The water is a totality uniting opposites manifested in different planes. The harmony and beauty is created by the fusion of the darkness of the depths with the brilliance of light on its surface. Also, through the coincidence of the form with the bottom that gives integrity to the landscape.

For eastern landscapers, the painting allows one to look at their own interior, suggesting that the representation of landscape has a direct relationship with who we are. In this way, the whole represented beginning with the present duality in water is a reflection of human nature, also dual and integrated at the same time. The difference with the oriental would be in the choice of detail that obliges one to abstract and arrive at the essential that later is extended as a whole, ceasing to be the description of a specific location.

Would you place yourself in the traditional group of landscape artists?

Water is an element of the landscape, so in this way I am a landscape artist. However, I create a reinterpretation of the landscape from a new focus, looking from the detail to the whole. Besides that, I work with technique in an experimental way.

Who would be references for you?

I have historical influences, such as Leonardo, of whom I have read a lot and always admired for his technique and capacity for analysis. His study of water includes more than just color: interested in waves, he analyzed its luminous capacity, the reflection and refraction though it. I cite it in my work in the smears and the velatures with which I build the images of the backgrounds. Also Monet, for his treatment of shadow in the reflection of landscape in the water.

Other references are connected with the current interrogations of the painter: How does one reinterpret an image processed through media that creates a personal reality from the painting? Why paint if photography registers the reality with insuperable precision? Vija Celmins with his details, Chuck Close with his faces and Gerhard Richter with his pictorial liberties have responded through their works. In them their central inspirations revealed is the painting and the human touch that from them is processed their own reality. We coincide in a sensibility of time, where the eye of the painter is behind the medias.

From another visual language, a contemporary artist bound to the landscape is Olafur Eliasson, who with very experimental methods approaches the viewer to the luminous sensations and atmospheres of the exterior, translated to the interior of an exhibition room; like bringing water physically to the museum. I do this with an illusion, however we fix the gaze on the same element.

Do you consider yourself part of the Land Art trend?

Historically, Land Art was an important moment for landscape in art. They leave the gallery room and the studios and go directly to the place to work, with the elements that are there, presenting their work as a record of this intervention. They marked a trend and were a defense for sculpture, photography and installations related with the landscape. I do not intervene the water as they intervene the earth, but the act of going to the place, studying it for days establishes a similarity between me and this trend.

The video that accompanies the exposition is part of your experimentation over water and its liberties?

The video investigated the reflective capacity of the water from another visual medium. I exercised seeing what really happened upon re-mirroring the water upon turning around the image. Highlighting the dualism between the movement of the upper part of the current, the light, and the refracted part of the shade that remains static, fusing them together in a single image.

Your work is a piece of time in nature…

That recorded instant on this natural screen claims a new time in the pictorial process, being the strategy of return that allows us to contemplate the human convention that we encode as landscape. It is my own form of recreating nature through the infinite source of image and life that is water.

References:

– Schiller, Friedrich. Kallias o sobre la belleza. Editorial Tecnos. Primera edición. Madrid, 2000. P. 16. 249 pp.

El Mercurio

She has just inaugurated, in Galería Animal, her first individual exhibition. It reveals her original and surprising graphic work. “All landscapers have always looked towards the horizon; I look down”.

By: Magaly Arenas Zapata

To be surprised and astonished is a pleasant experience and one that an artist cannot always transmit to its audience. You will be surprised when coming face to face with the works of Patricia Claro. First of all, because you will realize that your eye has tricked you because what you believed you were seeing was not what you thought. And then, you will admire the meticulous job of the artist: every painting takes her at least four months of intense labor.

This artist’s exhibition is a tribute to water and landscape. She has had an atypical trajectory. She opted for Design as her professional career even though she came from a family that had always been surrounded by art and music. For example, she is the great-granddaughter of Enrique Swinburn.

After several years, her profession bloomed with such intensity that she decided to study Art in the Universidad Católica. She graduated in 2005.

-How did you come upon the water theme?

“It was intuitive and it has to do with my relation to a river in the south of Chile. I have a very hypnotizing connection to this place. It is a closed environment that changes constantly; it contains images that last for only a moment. Afterwards they are gone and you have the desire to rescue them, to make them yours.”

-There is a lot of spiritual contemplation when you observe water.

“There is a search for unity. Water, because of its transparency, absorbs all of its surroundings. Because of water I talk about landscape. In the water I find the duality of bottom and surface, shadow and light and the movement that draws the image. My method has to do with this mechanism of water.”

-The spectator is fooled at first, thinking your painting is a photograph. Is this part of the game? Is this what you were looking for?

“It’s part of a game of creating your own realism, playing with the image and modifying it for your own esthetical means with your subjectivity and your stamp. My realism is shown through the handling of the technique. I show a detail that is at the limit of being abstract but it is in fact real.”

“From far away it may be perceived as a photograph but as you get closer there is a change of vision. To have two readings of the image makes it richer.”

-It’s curious that you define yourself as a landscaper.

“All landscapers have always looked towards the horizon; I look down, like a satellite, where I find what is reflected on top. This shows me the surroundings and the bottom.”

“I look for complete synthesis to talk about landscape. I am at the limit between realism and abstraction.”

-You spend hours observing water and light at different hours of the day, just like impressionists. Is there some impressionism in your work?

“There is much of Monet, of his vision in his own pond, but it is a vision that differs in time. I use other parameters to build the work: there is a technical vision involved that ends up modifying the image. I also use a treatment of shadows to see what is in the water.”

“It’s a colder work, more mathematical. My path in the place is not pictorial, I slide the place to my landscape; I make a post-landscape.”

What happens when an expert paints with a kid with a development disability? Look at me Foundation, that works for the inclusion of kids with special needs in the chilean educational system invited 20 artists to do exactly this. I was paired with the lovely Valentina Soto, you can see her work in the gallery below. Read more →

UWANTART is a new contemporary art gallery in Shanghai, China. For its opening exhibition they had local chinese artists and a few foreign ones, wich i was proudly part of. Read more →

By Joaquín Cociña

“I am writing, certainly, without having seen the exhibition, composing a text out of bits of the project, the photos, the conversations; maybe writing this is a little like writing fantastic literature. In any case, it’s an exercise to open a conversation about the exhibition”1.

Writing about the work En Tránsito had me troubled, but I got out thanks to that brief text from Adriana Valdés. I only had seen “live” some of the participant’s artworks. The majority had come to me attached, compressed, mediated in its most radical and semi-private term: e-mail.

The ones who study Art in South America and take Occidental Art History courses, receive an education based on different types of lighting projections one after another, while a professor explains the materiality of Rembrandt’s paintings, the North American painting dimensions in the 60’s… And where a Lucian Freud of 40 x 70 cm and 2 cm of depth, becomes a 200 x 230 cm image without a thickness.

Being sorry is inoperative. The point is that for an art student, historic paintings are projected files, but for that same student and future artist, the act of painting is a material job, like all pictorial acts.

That fact that painting has turned to photography and the mediated images has not resolved the problem. That which Benjamín called aura –term over chewed on, but inevitably ductile- shows us that the paintings we seem to appreciate are far away, a lot farther than our computer screens. What we see is residual, a radicalization of the copy and original problems. To doubt if there’s an original or not doesn’t work very much, it gives freedom sensations, but overwhelms.

In a past exhibition, while I was hanging a series of drawings, the local guard said to me: “…the photos are pretty”. As I explained to him that they were drawings and not photos, he asked me: “And how long did it take you to make the photos?”. I then understood that for him, a photo is not an analog or digital photosensible print, but an image that corresponds to a certain type. A blurred line separates the different types of images that are produced and perceived. Then, in that indetermination, it is worth asking which the space in where painting plays in is.

En Tránsito is a painting exhibition. It’s not a version or a rereading, the artworks present themselves as traditional paintings. But it’s the treatment and the references that make them to group in a problematic manner. The works have photography and other images as a reference, but also they have the immanent presence of the relationship between copy and original, merged in an affective bond of the image.

The artists of En Tránsito know that the images are coded, they know that it’s not the same to pretend to paint “what it’s seen” than painting absorbing elements of other codes, but their paintings face their references affectively. Barthes would probably be happy, but would say that those paintings have lost their punctum. On the other hand, Gerhard Ritcher once said that he painted based on photos to give these last ones a sense and direction. What’s left? A confusion. And in that confusion between the original and copy, between reference, image and surface, between coldness and affection, it can be talked about a transit between different points. But that confusion, where a no less confused painting is inserted, has a clear ending point: an exhibition that’s attended, where the old movement of confronting the paintings and seeing them live is produced, with all the material aspects that are blurred as they are formatted. Maybe that’s the space in which painting plays: the physical space, concrete and performative in which the artworks are set to be seen.

Finally, a last question without an answer. We should remember –How to forget it?- that these paintings are South American, people located in a place where there’s not precisely a lack of limits and definitions that can be celebrated as a post modern achievement. If the problem or the situation is the blurred line and the transit between the images and the similarity, the not central role of Latin American painters cannot be ignored. The action of painting is already a weird assimilation, taken out of proportion (as Valdés would say). But –and not as an answer, but as an escape route- that problem of uncertainty is present, as it’s already said, in the artistic education. If taking this as a virtue is irresponsibility, ignoring it is even worse.

Art and Letters. El Mercurio

WALDEMAR SOMMER

Sunday, July 29, 2007

Until September 23:

YENNYFERTH BECERRA and other 14 artists “Haber” MAVI

The installation genre is not free from the reiterative academicism of fairly worn out

formulas. That´s what we prove in the actual group of 13 pieces of work of that kind,

that the MAVI proposes us. Less known names dominate here; nevertheless, we find

some attractive authors. Four more experimented artists stand out. Without a doubt,

the pair Catalina Swinburn-Teresa Aninat proportions the most genuine and deeply

conceptual installation. It consists on a pair of big photos and an extent polyptych of

leather rectangles marked by fire with a key word and date; also, they form a central

cross. This way, it achieves the personal remembrance of a tragic event that has

included two opposite visions of the world. Formally well balanced, the contribution of

Yennyferth Becerra dyes itself of poetry through the white cables, of lights and golden

words; remembering the Brugnoli from years before. Isidora Correa, on the other hand,

falls back on her characteristic profiles of wooden furniture, this time fragmented.

Unfortunately, about the talented María José Ríos it must be said that her mass of

objects results superficial and, above all, incoherent.

Among the less experimented participants, Max Corvalán-Pincheira handles with an

imaginative humor two different identification cards, having the respective identificated

people act in a vehement way, in a digital video. Another sensitivity is the geometry of

Valeria Burgos. Her chromatic alternation of fluorescent tubes –in the line of the

Venezuelan Soto- deserved a much bigger special development. The house dust from

Santiago results the protagonist of Karen Fuenzalida. She captures it through a video

and a golden rug, under the television. For last, if Nicolás Grum knows how to make

sculptures and simple carton boxes playfully, Rodrigo Bruna retakes his peculiar material:

with bakery bags on the side, toasted bread form an ample mosaic of delicate

monochrome.

A lot less known artists than the previous mentioned are, in general, the 51 selected

painters of the MAC´s Concurso Marco Bontá. Few of them deserve to be

remembered. Of the three awarded, the only one to mention, just out of curiosity, is

Gonzalo Vargas’s canvas: a simple drawing obtained by the sun burn through a

magnifying glass. The contributions that do emerge convincing are from the well known

Sebatián Leyton –the magrittesque matter is very well painted, and ingeniously

presented-, from Patricia Claro, Felipe Cusicanqui, Bárbara Mödinger, Catalina Mena and

Christian Correa.

Watch out the imaginative plastic meaning of the pair Swinburn-Aninat, visually

materializing concepts of today’s special present.

Artes y Letras. EL MERCURIO.

Art Critique

Chiuminatto, Concha and Claro:

Waldemar Sommer

A typical pictorial theme, landscapes, has been interpreted in three different

ways by two female artists, in “Instituto Cultural de Las Condes”, and by a male artist

with trajectory, in “Sala Gasco”. This last painter mentioned, Pablo Chiuminatto, shows

new perspectives of an argument to which he has maintained himself loyal to. Read more →