Water Forms

When water runs out, there is nothing that can replace it.[1]

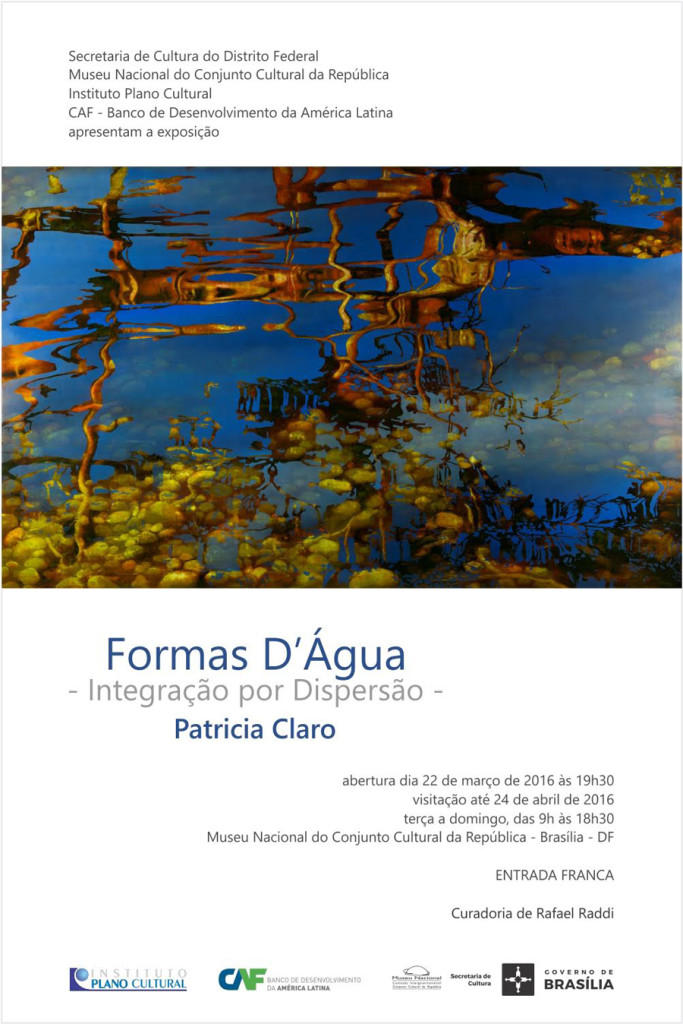

Patricia Claro started her investigative work on nature and the behavior of freshwater nearly a decade ago, placing this water resource –national and world heritage – as the object of her creation. Through a diligent research, she has perfected and refined her technique, through the decomposition of image layers, giving life to particular forms of water.

The sample contains a variety of pictorial, digital and manual elaborations, various languages that show a creative process that has been transformed into a work of art. The way to represent light through masked pictures, fabricated by delicate cut-outs, the artist reveals certain codes and figures of water. At the same time, the photographs are part of the archive of the path from which these codes of water deformation are extracted, drawn by beams of light united to a rhythmic motion. The video is the witness of this scenario in continuous change and renewal.

In the context of the overflow metaphor, which refers to the problem of freshwater shortage that the planet has been experiencing for years, Patricia’s work re-creates freshwater sources through images that convey the physicality of the water, through the dynamism between light, background and environment; which act as an extension and perpetuation of it, noting the infinity of images contained in each piece of river. The beauty of the images transmitted take the viewer to see the water again, but from a different valuation because the works of the artist discover the greatness contained in it, “making it talk”, so that it can communicate its content and memory to the viewer. Claro, through the technique used, lends water a way of expression: water is shown through the play of light that the artist is able to transfer from the river to the canvas, allowing it to be seen by countless viewers. By letting us get to know what water contains and expresses through the recreation of images, it leads the observer to consider water as an element worthy to be valued and protected. Thus, Claro’s paintings prolong and drag on their existence and, simultaneously, promote an awareness on the viewer about its preservation, to value it as an inexhaustible source of beauty.

When transfering the motion of the waves and currents, the artist discovers certain forms and signs that water reveals and represents, which resemble the characters in Chinese writing, as if an alphabet itself were contained in it. It is a meaning that attempts to be decoded to come to the exterior. However, in order to hear the water it would be necessary to spend hours in silence and admire it with absolute care and detail. With this purpose, the author goes to her source of fresh water in southern Chile, where – in a retreat of silence and contemplation – observes for hours, days, weeks and months the natural state of water, especially the transformations associated with seasonal changes. The digital record serves as a witness so that, when back in the studio, the multiplicity of images viewed can be recalled and associated with a unique deformation code that seems written on the the surface of water itself. This set of signs written by light and movement constitute the motive of the photographs that she presents, from which the phonemes that make up the language of water are removed.

The particular similarity between these aquatic ideograms and the Chinese calligrams is not casual. In the words of Ezra Pound, “(…) the Chinese notation is much more than arbitrary signs. It is based on a vivid shorthand picture of the operations of nature (…) The fact is that the acts are successive, even continuous; one is cause or succession of the other. ”[2] In this way, the photo sequence constitutes a story that contains information of nature, as well as water figures which have been cut and linearly exposed.

Water has the quality of being in constant motion and that is why the images that it emits when it recieves sunlight are endless, inexhaustible and exclusive: there will never be an exact repetition of the conditions of movement, light, flow, topography and climate , that allow a replica of any of the images delivered by the water.

What does water want to tell us? How can we interpret its writing? We know that it shows us the nature and reflection of the surrounding environment: trees, branches, clouds, earth and the sun itself; but the forms drawn by the light that appear in a sequencial order due to the continuous permanent move, seem to contain something more … What information is contained in them?

“The world is an immense Narcissus that is thinking.”[3] The water, like a mirror, reflects us… reminding us who we are, holding our identity.

Perhaps water contains the memory of the history of mankind. If so, the need for its care and respect is presented as an uncompromising imperative: preserve freshwater sources is to preserve the legacy of man.

References

Bachelard, G. El agua y los sueños. Fondo de Cultura Económica. Mexico, 2003.

Fenollosa, E., Poud, E., El carácter de la escritura china como medio poético. Translation of Mariano Antolín Rato. Ed. Visor. Madrid, 1977.

Shiva, V. Las guerras del agua. Ed. Icaria. Barcelona, 2002. Vandana Shiva, Indian scientist and philosopher who has devoted much of her research to the problem of water, current director of the Research Foundation for Science, Technology and Natural Resource Policy.

[1] Shiva, Vandana. Las guerras del agua. Editorial Icaria. Barcelona, 2002. P. 32.

[2]Fenollosa, Ernest; Poud, Ezra. El carácter de la escritura china como medio poético. Traducción de Mariano Antolín Rato. Editorial Visor. Madrid, 1977. Pp. 33-37.

[3] Gasquet, Joachim. Narciso, p. 45. En: Gastón Bachelard, El agua y los sueños. Fondo de Cultura Económica. México, 2003.